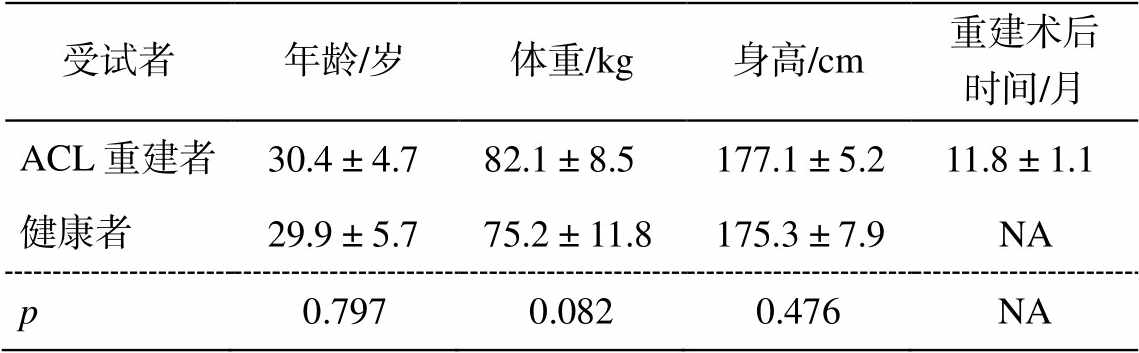

表1 受试者基本信息

Table 1 Demographics of the participants

受试者年龄/岁体重/kg身高/cm重建术后时间/月 ACL重建者30.4 ± 4.782.1 ± 8.5177.1 ± 5.211.8 ± 1.1 健康者29.9 ± 5.775.2 ± 11.8175.3 ± 7.9NA p0.7970.0820.476NA

北京大学学报(自然科学版) 第59卷 第3期 2023年5月

ActaScientiarumNaturaliumUniversitatisPekinensis, Vol. 59, No. 3 (May 2023)

doi: 10.13209/j.0479-8023.2023.032

北京大学第三医院创新转化基金(BYSYZHKC2020106)、北京大学第三医院优秀留学回国人员科研启动基金(BYSYLXHG2020007)、北京大学第三医院临床重点项目(BYSYZD2021012)、北京市自然科学基金(7202232)和中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金(2022QN007)资助

收稿日期: 2022–05–20;

修回日期: 2022–07–28

摘要 为了分析前交叉韧带(ACL)重建术后 12 个月患者的大腿肌肉在不同屈膝角度时的等速肌力特征, 对 16 名 ACL 重建术后 12 个月的患者和 14 名健康对照者在 60°/s 的角速度下进行股四头肌和腘绳肌的等速向心和离心开链肌力测试, 分析不同等速收缩模式下的肌力峰值及不同屈膝角度时的肌力, 并计算腘绳肌与股四头肌等速向心肌力比值(Hc/Qc)、离心肌力比值(He/Qe)、腘绳肌离心与股四头肌向心肌力比值(He/Qc)和腘绳肌向心肌力与股四头肌离心肌力比值(Hc/Qe)。应用混合设计双因素方差分析方法, 检验不同人群和不同侧别对大腿等速肌力特征的影响。结果表明, 腘绳肌等速肌力在不同屈膝角度时的特征相似, ACL 重建侧显著小于对侧, 与健康对照者无显著差异。股四头肌等速肌力呈现角度特异性, 屈膝 40°和 50°时重建侧的股四头肌等速向心肌力不仅与对侧存在差异, 也与健康人群不同, 是更具特异性的评估肌力特征指标。在康复过程中, 不仅要关注双侧对称性, 而且要关注其是否恢复到健康者的水平, 强调特定角度下肌肉功能的恢复。较小屈膝角度下, 双侧下肢的功能性屈伸肌力比值与健康人群均呈现差异, 提示术后康复不仅要加强重建侧屈膝动作的控制训练, 也要同时改善对侧的缓冲控制能力。

关键词 前交叉韧带重建; 等速肌力; 股四头肌; 腘绳肌; 康复

前交叉韧带(anterior cruciate ligament, ACL)断裂后无法自然愈合, 通常需要进行 ACL 重建手术。尽管 ACL 重建手术通常可以很好地提高膝关节的稳定性, 但研究表明 ACL 重建后总体再伤率高达15%[1]; 重建术后 10~15 年, 患者的膝骨关节炎发生率为 80%[2]。

ACL 重建术后普遍存在大腿肌力减弱的特征, 即使在患者重返运动后, 股四头肌力量不足依然很常见。ACL 重建术后两年的患者仍然存在股四头肌肌力不足的特点[3]。股四头肌力量下降不仅与 ACL重建术后运动模式的改变[4–5]和功能表现[5–7]显著相关, 而且与潜在的生物力学危险因素相关[8–9]。研究表明, 股四头肌肌力不足者重返运动后, 在随后的 5 年内更易发生膝软骨的早期退变[10]。因此, ACL 重建术后恢复大腿肌肉力量对重返运动以及预防继发性损伤至关重要[11]。

ACL 重建术后的肌力特征越来越受到关注。目前的研究多以 ACL 重建者对侧为参照, 分析重建侧与对侧等速肌力的差异, 并根据双侧肌力的对称性来评价肌力的恢复情况[12–15], 常作为患者术后重返运动的重要标准之一[16]。术后重返运动时, 股四头肌力量不对称的患者在一年后膝关节的功能表现比双侧肌力对称者更差[17], 膝关节功能评分更高者的重建侧股四头肌力量更强, 双侧肌力的对称度也更高[13]。此外, 腘绳肌(hamstring, H)与股四头肌(quadriceps, Q)峰值肌力的比值(H/Q)也是目前评估肌力平衡、膝关节稳定状态以及整体功能状态的另一类重要指标[18–19]。但是, 现有的研究无论是对于对称性的评估还是屈伸肌力比值的分析, 多基于峰值肌力计算, 较少关注不同屈膝角度下的肌力值。不同屈膝角度对应不同的功能状态和肌力需求。也有研究通过分析不同屈膝角度的肌力值, 揭示单侧ACL 断裂患者[20–21]和 ACL 重建患者[22]的肌力状态, 但均以对侧为对照, 没有比较与健康人群的差异。由于 ACL 重建术后对侧的功能状态也可能受到影响, 仅以对侧为参照并不能全面揭示其特异性改变, 因此, 我们不仅要关注重建侧与对侧之间的对称性, 更要关注 ACL 重建者与健康人群的组间差异[23]。

本研究通过探究单侧 ACL 重建术后患者重返运动后的股四头肌和腘绳肌在不同屈膝角度时的肌力特征, 为提高 ACL 重建术后康复效果提供理论依据。本研究将验证以下假设: 1)单侧 ACL 重建术后患者, 重建侧股四头肌肌力与对侧及健康对照者之间均存在显著差异, 且具有角度特异性; 2)重建侧的腘绳肌肌力与对侧及健康对照者之间均存在显著的差异, 且具有角度特异性; 3)重建侧的腘绳肌与股四头肌肌力比值与对侧及健康对照者之间均存在显著的差异, 且具有角度特异性。

本研究共招募单侧 ACL 重建术后 12 个月(重建术后距离测试时间为 11.8±1.1 月)的男性患者 16 名(7 名为右侧重建, 9 名为左侧重建), 男性健康受试者 14 名, 具体信息如表 1 所示。入组的 ACL 重建者均为单侧自体腘绳肌腱重建, 无同时进行的其他结构的合并手术, 下肢无其他外科手术史。健康受试者无下肢外伤史及其他影响运动功能的疾病。所有患者进行ACL 重建术后, 均按照北京大学第三医院运动医学科相应的康复方案进行康复训练。测试前, 研究方案经过北京大学第三医院医学伦理委员会同意, 且所有受试者均已签署知情同意书。

表1 受试者基本信息

Table 1 Demographics of the participants

受试者年龄/岁体重/kg身高/cm重建术后时间/月 ACL重建者30.4 ± 4.782.1 ± 8.5177.1 ± 5.211.8 ± 1.1 健康者29.9 ± 5.775.2 ± 11.8175.3 ± 7.9NA p0.7970.0820.476NA

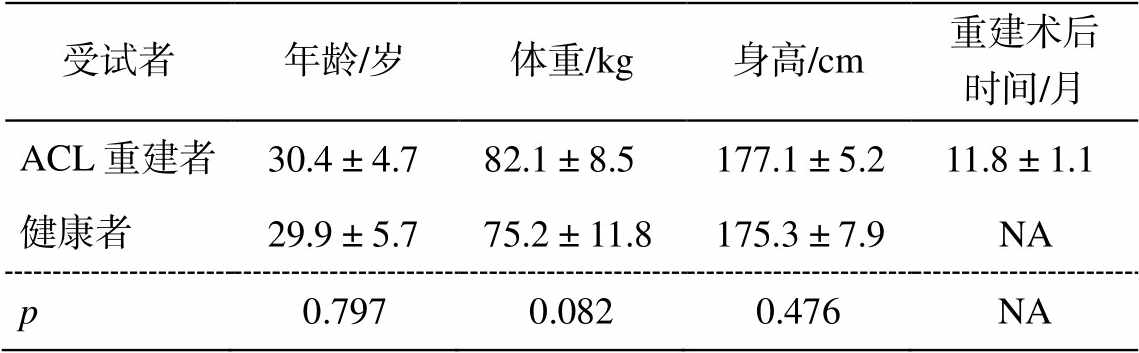

应用等速肌力测试系统(Contrex MJ), 对股四头肌和腘绳肌分别进行 60°/s 向心收缩、60°/s 离心收缩两种模式下的开链肌力测试, 测试范围为屈膝90°~20°。测试时, 受试者躯干屈曲角为 120°, 测试前要求受试者尽量放松, 以便进行去重力测试。每种收缩模式下的肌力重复测试 5 次, 相邻收缩模式测试间隔为 3 分钟以便休息大腿肌群。患者每次均先测对侧, 再测重建侧; 健康受试者每次均先测优势侧, 再测非优势侧(将健康人群的踢球腿定义为优势侧, 另一侧定义为非优势侧)。等速肌力测试装置如图 1 所示。

等速肌力参数主要包括向心收缩模式(concent-ric)下的股四头肌肌力(Qc)和腘绳肌肌力(Hc)的峰值以及屈膝角度为 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Qc 和 Hc; 离心收缩模式(eccentric)下的股四头肌肌力(Qe)和腘绳肌肌力(He)的峰值以及屈膝角度为 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Qe和 He。为了探究能更好地反映肌肉生理特性的指标, 进一步分析传统性与功能性腘绳肌与股四头肌的比值。传统性腘绳肌与股四头肌的比值包括腘绳肌等速向心肌力(Hc)与股四头肌等速向心肌力(Qc)的比值(Hc/Qc)以及腘绳肌等速离心肌力(He)与股四头肌等速离心肌力(Qe)的比值(He/Qe), 功能性腘绳肌与股四头肌比值包括腘绳肌等速向心肌力与股四头肌等速离心肌力比值(Hc/Qe)以及腘绳肌等速离心肌力与股四头肌等速向心肌力比值(He/Qc)[21]。以身高与体重的乘积 (BW×BH) 对肌力矩进行标准化。

应用混合设计双因素方差分析(ANONA)方法, 检验不同人群(ACL 重建者和健康对照者)和不同侧别(ACL重建者的重建侧和对侧, 健康对照者的优势侧和非优势侧)对等速肌力的影响, 整体显著性水平定义为 0.05。若不同人群和不同侧别两因素存在交互效应, 则分别对人群和侧别两个因素进行后续检验: 应用配对 t 检验方法, 分析 ACL 重建者重建侧与对侧之间、健康者优势侧与非优势侧之间的差异; 应用独立样本 t 检验方法, 分析 ACL 重建者重建侧与健康者非优势侧、ACL 重建者对侧与健康者优势侧的差异。共进行 4 次后续检验, 对统计结果进行 Bonfer-roni 矫正, 因此后续检验中的显著性水平为 0.05/4=0.0125。本研究中所有统计分析均采用 SPSS16.0 软件完成。

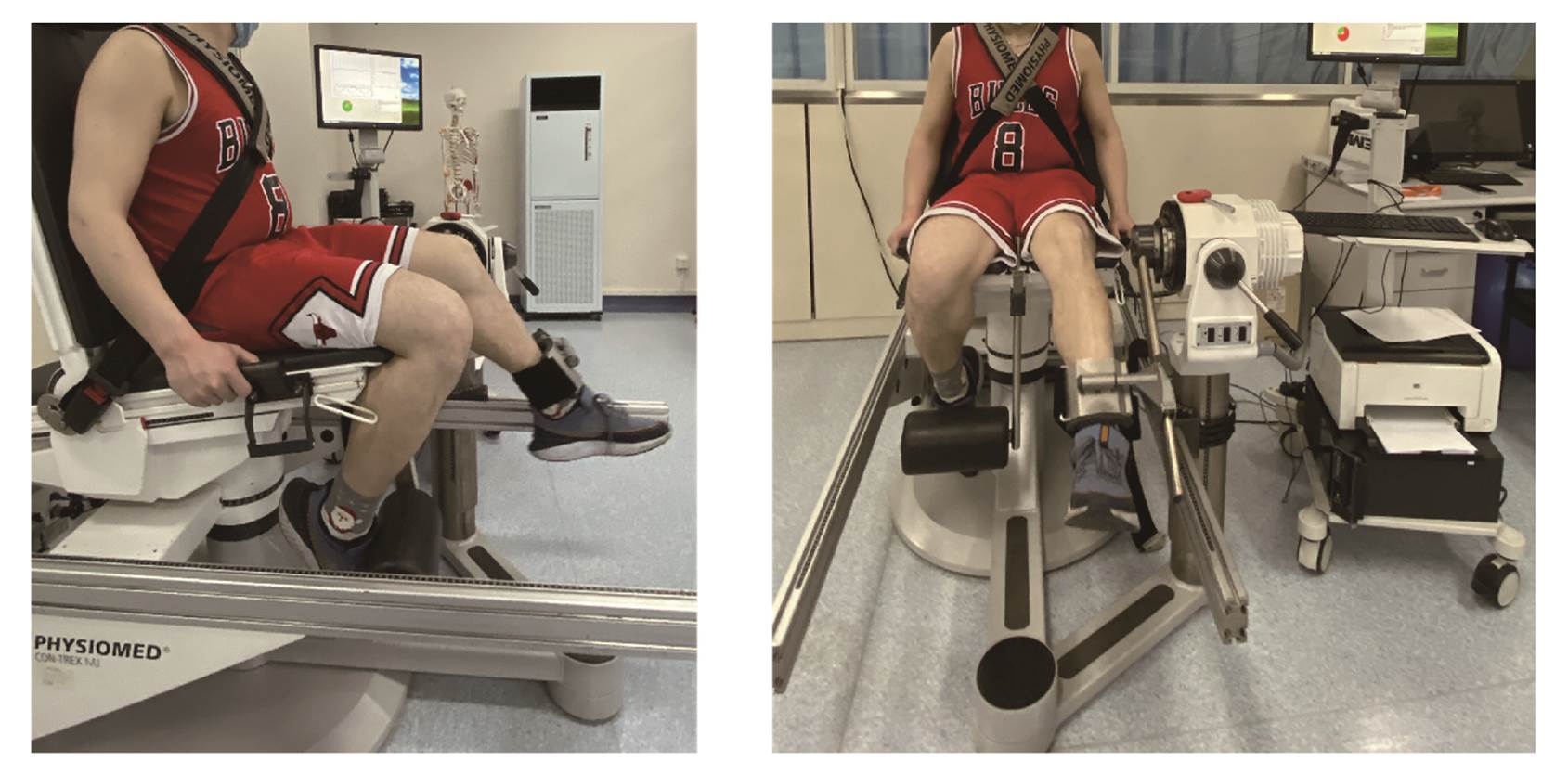

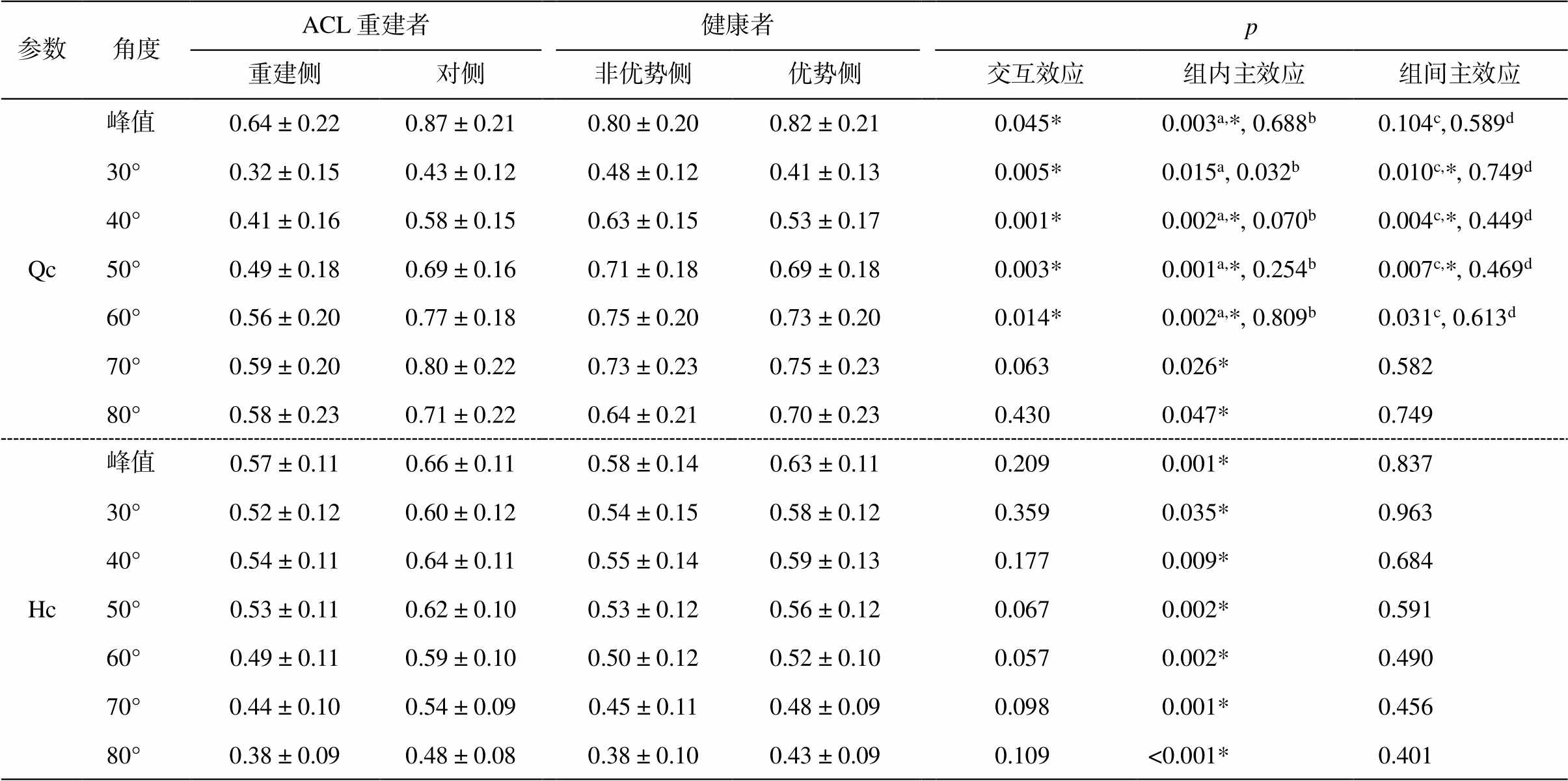

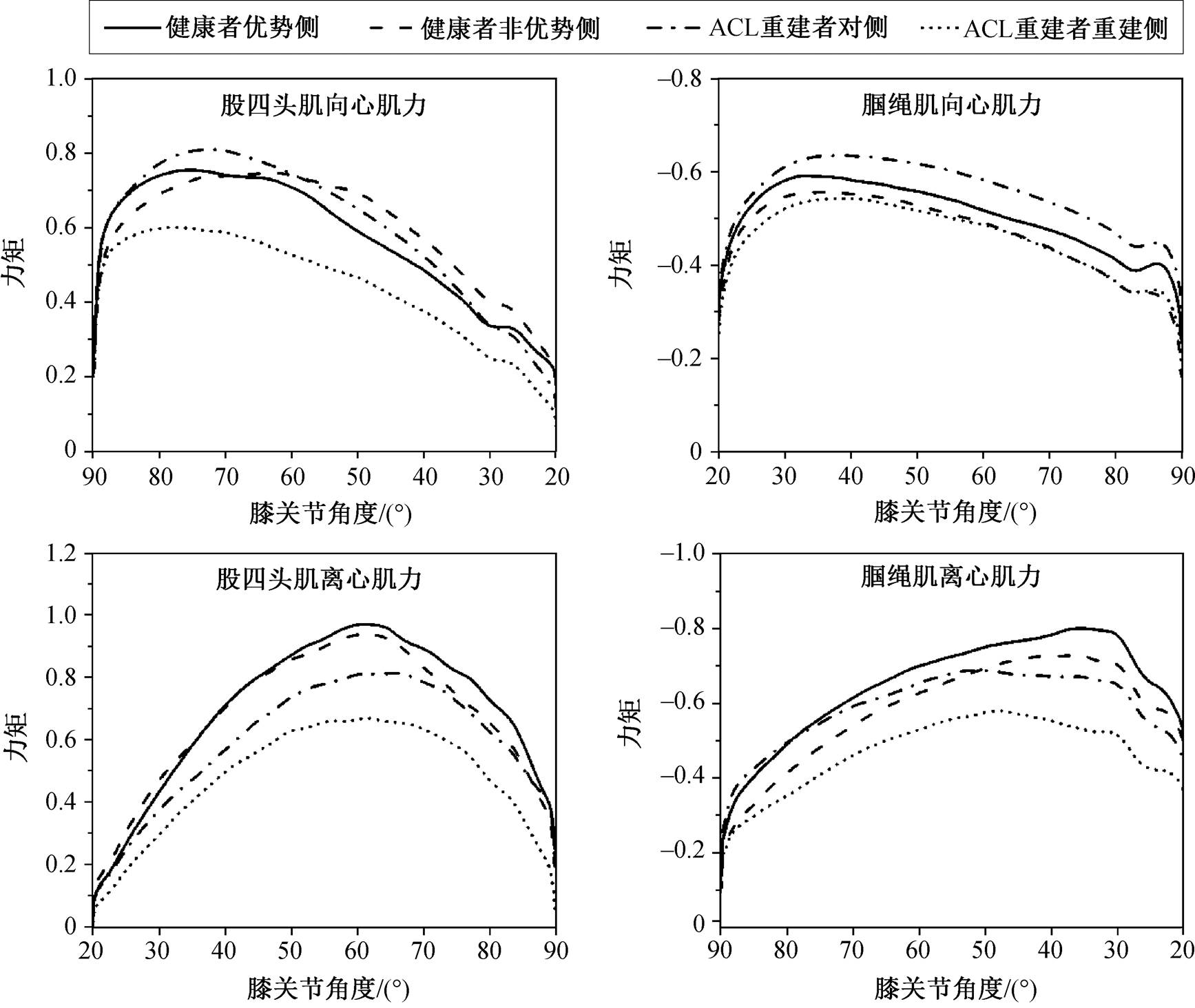

如表 2 和图 2 所示, 不同人群和不同侧别对 Qc的峰值存在显著交互效应(p=0.045)。后续检验结果表明, ACL 重建者重建侧的 Qc 峰值显著小于对侧(p=0.003), 健康者非优势侧与优势侧之间的Qc 峰值无显著差异(p=0.688)。ACL 重建者的重建侧 Qc 峰值与健康者的非优势侧无显著差异(p= 0.104), ACL 重建者对侧的 Qc 峰值与健康者的优势侧也无显著差异(p=0.589)。

屈膝 30°时, 不同人群和不同侧别的 Qc 存在显著的交互效应(p=0.005)(表 2)。后续检验结果表明, 屈膝 30°时, ACL 重建者与健康者双侧之间的 Qc 均无显著差异(p=0.015, p=0.032), ACL 重建者重建侧的 Qc 显著小于健康者的非优势侧(p=0.010), 而对侧与健康者的优势侧无显著差异(p=0.749)。

图1 等速肌力测试装置

Fig. 1 Testing device of isokinetic muscle strength test

表2 股四头肌和腘绳肌的等速向心肌力参数

Table 2 Concentric strength of the quadriceps and hamstrings

参数角度ACL重建者健康者p 重建侧对侧非优势侧优势侧交互效应组内主效应组间主效应 Qc 峰值0.64 ± 0.220.87 ± 0.210.80 ± 0.200.82 ± 0.210.045*0.003a,*, 0.688b0.104c,0.589d 30°0.32 ± 0.150.43 ± 0.120.48 ± 0.120.41 ± 0.130.005*0.015a, 0.032b0.010c,*, 0.749d 40°0.41 ± 0.160.58 ± 0.150.63 ± 0.150.53 ± 0.170.001*0.002a,*, 0.070b0.004c,*, 0.449d 50°0.49 ± 0.180.69 ± 0.160.71 ± 0.180.69 ± 0.180.003*0.001a,*, 0.254b0.007c,*, 0.469d 60°0.56 ± 0.200.77 ± 0.180.75 ± 0.200.73 ± 0.200.014*0.002a,*, 0.809b0.031c, 0.613d 70°0.59 ± 0.200.80 ± 0.220.73 ± 0.230.75 ± 0.230.0630.026*0.582 80°0.58 ± 0.230.71 ± 0.220.64 ± 0.210.70 ± 0.230.4300.047*0.749 Hc峰值0.57 ± 0.110.66 ± 0.110.58 ± 0.140.63 ± 0.110.2090.001*0.837 30°0.52 ± 0.120.60 ± 0.120.54 ± 0.150.58 ± 0.120.3590.035*0.963 40°0.54 ± 0.110.64 ± 0.110.55 ± 0.140.59 ± 0.130.1770.009*0.684 50°0.53 ± 0.110.62 ± 0.100.53 ± 0.120.56 ± 0.120.0670.002*0.591 60°0.49 ± 0.110.59 ± 0.100.50 ± 0.120.52 ± 0.100.0570.002*0.490 70°0.44 ± 0.100.54 ± 0.090.45 ± 0.110.48 ± 0.090.0980.001*0.456 80°0.38 ± 0.090.48 ± 0.080.38 ± 0.100.43 ± 0.090.109<0.001*0.401

注: *表示交互效应和主效应显著; a 表示 ACL 重建者的重建侧与对侧之间比较; b 表示健康者的非优势侧与优势侧之间比较; c 表示 ACL 重建者的重建侧与健康者的非优势侧之间比较; d 表示ACL 重建者的对侧与健康者的优势侧之间比较。下同。

图2 股四头肌和腘绳肌等速肌力曲线图

Fig. 2 Graph of isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring strength

屈膝 40°, 50°和 60°时, 不同人群和不同侧别在的 Qc 存在显著的交互效应(p=0.001, p=0.003, p =0.014)。后续检验结果表明, 屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建者重建侧的 Qc 均显著小于对侧和健康者的非优势侧(p≤0.007)。屈膝 60°时, 重建侧的 Qc 显著小于对侧(p=0.002), 而与健康者的非优势侧无显著差异(p=0.031)。屈膝 40°, 50°和 60°时, 健康者非优势侧和优势侧之间的 Qc 均无显著差异(p=0.070, p=0.254, p=0.809), ACL重建者对侧的 Qc 与健康者的优势侧也均无显著差异(p=0.449, p=0.469, p= 0.613)。

屈膝 70°和 80°时, 不同人群和不同侧别的 Qc均不存在交互效应(p=0.063, p=0.430), ACL 重建者与健康者之间的 Qc 均无显著差异(p=0.582, p= 0.749), 但两组人群不同侧别之间存在显著差异(p= 0.026, p=0.047)。

不同人群以及不同侧别对 Hc 的峰值以及屈膝30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的Hc均不存在交互效应(p≥0.057)。ACL 重建者与健康者之间的 Hc 均无显著差异(p≥0.401), 但两组人群不同侧别之间存在显著差异(p ≤ 0.035)。

如表 3 所示, 在屈膝 30°时, 不同人群和不同侧别的 Qe 存在显著的交互效应(p=0.005)。后续检验结果表明, ACL 重建者的重建侧 Qe 显著小于健康者的非优势侧(p=0.002), 对侧的 Qe 与健康者的优势侧之间无显著差异(p=0.460)。ACL 重建者和健康者双侧之间的 Qe 均无显著差异(p=0.032, p= 0.028)。

不同人群和不同侧别的 Qe 峰值以及屈膝 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Qe 均不存在交互效应(p≥ 0.051)。ACL 重建者与健康者之间的上述 Qe 均无显著差异(p≥0.056)。屈膝 40°和 50°时, 两组人群不同侧别之间均无显著差异(p≥0.090), 但对于 Qe 峰值以及屈膝 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Qe, 两组人群不同侧别之间存在显著差异(p≤0.012)。

不同人群和不同侧别的 He 峰值以及屈膝 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和80°时的 He 均不存在交互效应(p≥0.159)。ACL 重建者与健康者之间的 He 均无显著差异(p≥0.358), 但两组人群不同侧别之间存在显著差异(p≤0.005)。

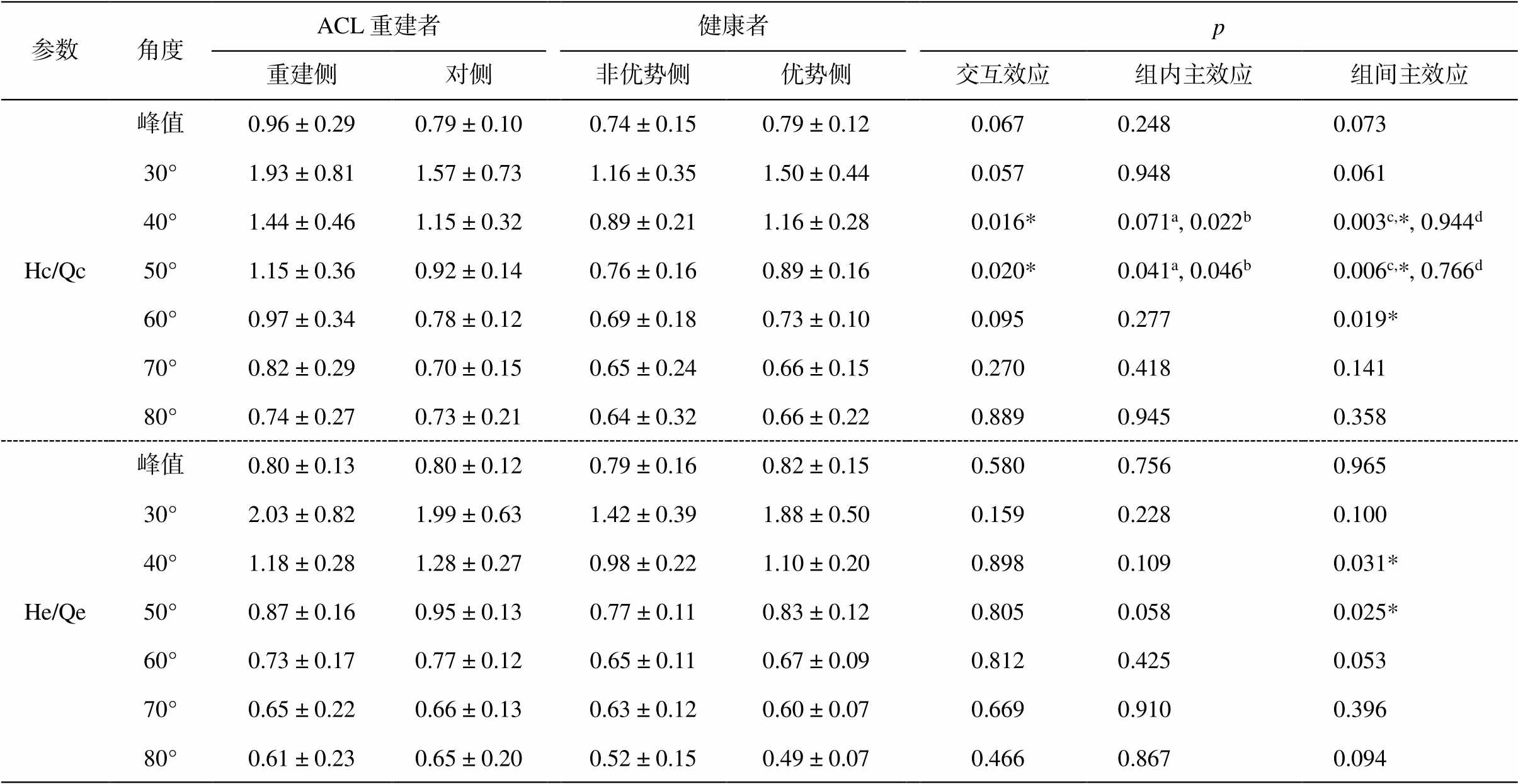

如表 4 所示, 屈膝 40°和 50°时, 不同人群和不同侧别的 Hc/Qc 均存在显著的交互效应(p=0.016, p=0.020)。后续检验结果表明, 屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建者重建侧与对侧之间的 Hc/Qc 均无显著差异(p=0.071, p=0.041), 健康者非优势侧和优势侧之间的 Hc/Qc 也均无显著差异(p=0.022, p=0.046)。屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建者重建侧的 Hc/Qc 均显著大于健康者的非优势侧(p=0.003, p=0.006), 而对侧的 Hc/Qc 与健康者的优势侧均无显著差异(p=0.944, p=0.766)。

表3 股四头肌和腘绳肌的等速离心肌力参数

Table 3 Eccentric strength of the quadriceps and hamstrings

参数角度ACL重建者健康者p 重建侧对侧非优势侧优势侧交互效应组内主效应组间主效应 Qe峰值0.87 ± 0.241.04 ± 0.240.98 ± 0.201.06 ± 0.090.2830.003*0.421 30°0.34 ± 0.110.39 ± 0.130.49 ± 0.060.43 ± 0.080.005*0.032a, 0.028b0.002c,*, 0.460d 40°0.56 ± 0.180.61 ± 0.180.71 ± 0.110.70 ± 0.070.0510.4800.056 50°0.72 ± 0.220.80 ± 0.230.85 ± 0.200.86 ± 0.100.1920.0900.275 60°0.79 ± 0.230.90 ± 0.250.91 ± 0.220.98 ± 0.100.5700.012*0.247 70°0.78 ± 0.270.92 ± 0.240.82 ± 0.210.95 ± 0.110.9570.006*0.662 80°0.64 ± 0.220.77 ± 0.210.64 ± 0.270.83 ± 0.140.3880.001*0.750 He峰值0.68 ± 0.150.83 ± 0.210.76 ± 0.170.88 ± 0.200.603<0.001*0.358 30°0.61 ± 0.130.75 ± 0.230.69 ± 0.190.81 ± 0.220.8430.003*0.371 40°0.62 ± 0.150.76 ± 0.220.69 ± 0.160.77 ± 0.180.4020.005*0.575 50°0.61 ± 0.150.75 ± 0.190.65 ± 0.130.72 ± 0.150.159<0.001*0.943 60°0.55 ± 0.140.68 ± 0.170.59 ± 0.110.67 ± 0.110.198<0.001*0.879 70°0.47 ± 0.120.59 ± 0.140.49 ± 0.080.58 ± 0.090.238<0.001*0.943 80°0.36 ± 0.090.46 ± 0.110.37 ± 0.100.43 ± 0.090.233<0.001*0.732

表4 传统腘绳肌与股四头肌力量比值

Table 4 Traditional ratio of hamstring to quadriceps strength

参数角度ACL重建者健康者p 重建侧对侧非优势侧优势侧交互效应组内主效应组间主效应 Hc/Qc峰值0.96 ± 0.290.79 ± 0.100.74 ± 0.150.79 ± 0.120.0670.2480.073 30°1.93 ± 0.811.57 ± 0.731.16 ± 0.351.50 ± 0.440.0570.9480.061 40°1.44 ± 0.461.15 ± 0.320.89 ± 0.211.16 ± 0.280.016*0.071a, 0.022b0.003c,*, 0.944d 50°1.15 ± 0.360.92 ± 0.140.76 ± 0.160.89 ± 0.160.020*0.041a, 0.046b0.006c,*, 0.766d 60°0.97 ± 0.340.78 ± 0.120.69 ± 0.180.73 ± 0.100.0950.2770.019* 70°0.82 ± 0.290.70 ± 0.150.65 ± 0.240.66 ± 0.150.2700.4180.141 80°0.74 ± 0.270.73 ± 0.210.64 ± 0.320.66 ± 0.220.8890.9450.358 He/Qe峰值0.80 ± 0.130.80 ± 0.120.79 ± 0.160.82 ± 0.150.5800.7560.965 30°2.03 ± 0.821.99 ± 0.631.42 ± 0.391.88 ± 0.500.1590.2280.100 40°1.18 ± 0.281.28 ± 0.270.98 ± 0.221.10 ± 0.200.8980.1090.031* 50°0.87 ± 0.160.95 ± 0.130.77 ± 0.110.83 ± 0.120.8050.0580.025* 60°0.73 ± 0.170.77 ± 0.120.65 ± 0.110.67 ± 0.090.8120.4250.053 70°0.65 ± 0.220.66 ± 0.130.63 ± 0.120.60 ± 0.070.6690.9100.396 80°0.61 ± 0.230.65 ± 0.200.52 ± 0.150.49 ± 0.070.4660.8670.094

不同人群和不同侧别对向心肌力峰值的比值Hc/Qc 以及屈膝 30°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Hc/Qc 均不存在交互效应(p≥0.057)。两组人群不同侧别之间的Hc/Qc 均无显著差异(p≥0.248)。对于峰值比值 Hc/ Qc 以及屈膝 30°, 70°和 80°时的 Hc/Qc, ACL 重建者与健康者相似(p≥0.061), 但 ACL 重建者屈膝 60°时的 Hc/Qc 显著大于健康者(p=0.019)。

不同人群以及不同侧别对离心肌力峰值的比值He/Qe 以及屈膝 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的He/Qe 均不存在交互效应(p≥0.159)。两组人群不同侧别之间的 He/Qe 无显著差异(p≥0.058)。对于峰值比值 He/Qe 以及屈膝 30°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的 He/Qe, ACL 重建者与健康者相似(p≥0.053), 但在屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建者的 He/Qe 均显著大于健康者(p =0.031, p=0.025)。

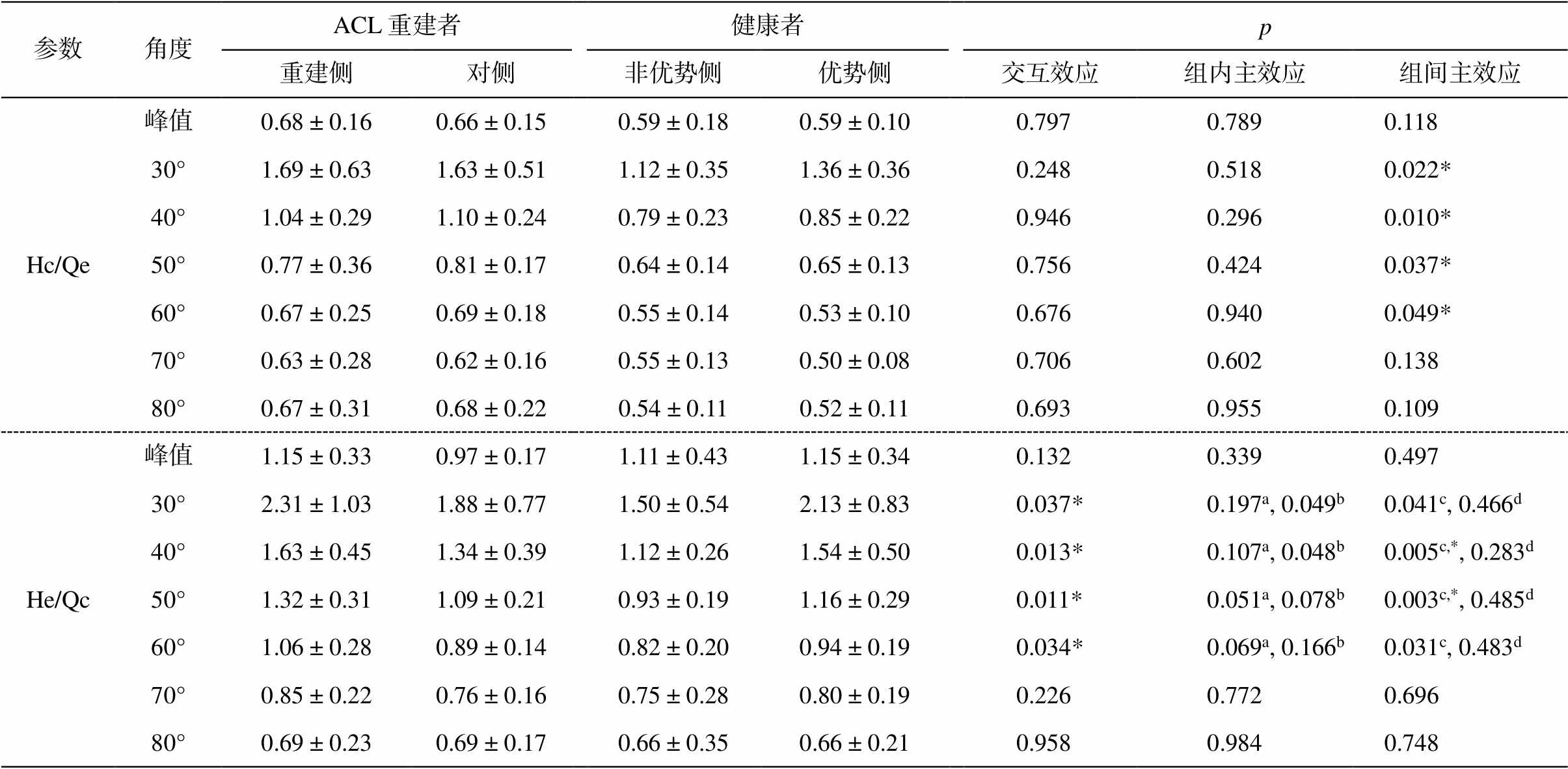

如表 5 所示, 不同人群和不同侧别对峰值肌力比值 Hc/Qe 以及屈膝 30°, 40°, 50°, 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Hc/Qe 均不存在交互效应(p≥0.248)。在上述情况下, 两组人群不同侧别之间均无显著差异(p≥ 0.296)。在屈膝 30°, 40°, 50°和 60°时, ACL 重建者的 Hc/Qe 显著大于健康者(p≤0.049), 但对于峰值肌力比值 Hc/Qe 以及屈膝 70°和 80°时的 Hc/Qe, 则不存在显著的组间差异(p≥0.109)。

在屈膝 40°和 50°时, 不同人群和不同侧别的He/Qc 均存在显著的交互效应(p=0.013, p=0.011)。后续检验结果表明, 屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建 者和健康者双侧之间的 He/Qc 均无显著差异(p≥ 0.048)。屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建者重建侧的He/Qc 均显著大于健康者的非优势侧(p=0.005, p= 0.003), 而对侧的 He/Qc 与健康者的优势侧均无显著差异(p=0.283, p=0.485)。

在屈膝 30°和 60°时, 不同人群和不同侧别的He/Qc 存在交互效应(p=0.013, p=0.034)。后续检验结果表明, ACL 重建者和健康者双侧下肢之间的He/Qc 均无统计学差异(p≥0.049), ACL 重建者重建侧与对侧的 He/Qc 与健康者的非优势侧和优势侧之间亦无统计学差异(p≥0.031)。

不同人群和不同侧别对峰值肌力比值 He/Qc 以及屈膝 70°和 80°时的 He/Qc 均不存在交互效应(p≥0.132)。ACL 重建者与健康者之间的 He/Qc 无显著差异(p ≥ 0.497), 两组人群不同侧别之间也无显著差异(p ≥ 0.339)。

表 5 功能性腘绳肌与股四头肌力量比值

Table 5 Functional ratio of hamstring to quadriceps strength

参数角度ACL重建者健康者p 重建侧对侧非优势侧优势侧交互效应组内主效应组间主效应 Hc/Qe峰值0.68 ± 0.160.66 ± 0.150.59 ± 0.180.59 ± 0.100.7970.7890.118 30°1.69 ± 0.631.63 ± 0.511.12 ± 0.351.36 ± 0.360.2480.5180.022* 40°1.04 ± 0.291.10 ± 0.240.79 ± 0.230.85 ± 0.220.9460.2960.010* 50°0.77 ± 0.360.81 ± 0.170.64 ± 0.140.65 ± 0.130.7560.4240.037* 60°0.67 ± 0.250.69 ± 0.180.55 ± 0.140.53 ± 0.100.6760.9400.049* 70°0.63 ± 0.280.62 ± 0.160.55 ± 0.130.50 ± 0.080.7060.6020.138 80°0.67 ± 0.310.68 ± 0.220.54 ± 0.110.52 ± 0.110.6930.9550.109 He/Qc峰值1.15 ± 0.330.97 ± 0.171.11 ± 0.431.15 ± 0.340.1320.3390.497 30°2.31 ± 1.031.88 ± 0.771.50 ± 0.542.13 ± 0.830.037*0.197a, 0.049b0.041c, 0.466d 40°1.63 ± 0.451.34 ± 0.391.12 ± 0.261.54 ± 0.500.013*0.107a, 0.048b0.005c,*, 0.283d 50°1.32 ± 0.311.09 ± 0.210.93 ± 0.191.16 ± 0.290.011*0.051a, 0.078b0.003c,*, 0.485d 60°1.06 ± 0.280.89 ± 0.140.82 ± 0.200.94 ± 0.190.034*0.069a, 0.166b0.031c, 0.483d 70°0.85 ± 0.220.76 ± 0.160.75 ± 0.280.80 ± 0.190.2260.7720.696 80°0.69 ± 0.230.69 ± 0.170.66 ± 0.350.66 ± 0.210.9580.9840.748

本文研究结果支持第一个假设, 即 ACL 重建侧股四头肌肌力与对侧及健康对照者之间均存在显著差异, 且具有角度特异性。本研究发现, ACL 重建者重建侧的股四头肌等速向心收缩和离心收缩时的肌力峰值均显著小于对侧, 仅呈现与对侧的差异, 而与健康对照者无显著差异, 股四头肌峰值肌力主要体现为双侧肌力的不对称特征。不同屈膝角度下,肌力不仅呈现与对侧的差异, 也呈现组间差异。屈膝 30°时, ACL 重建者双侧股四头肌的等速肌力虽无显著差异, 但重建侧的 Qc 显著小于健康对照者; 屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建者重建侧的 Qc 不仅与健康人群存在差异, 也与对侧存在差异。研究结果表明, ACL 重建者股四头肌等速向心肌力的差异性主要发生在屈膝 30°~50°时, 尤其在屈膝 40°和50°时。这与以往研究结果相似。Huang 等[20]通过分析单侧 ACL 断裂患者的等速肌力, 发现在屈膝40°和 50°时, 股四头肌的等速肌力与对侧的差异最大。此外, 最近有研究表明, ACL 重建术后 4 年, 股四头肌肌力仍然比健康人群弱[23], 并提出临床医生应该考虑将重建侧与健康者进行比较, 以便更科学地做出重返运动的决策。本文研究结果也表明, 在对 ACL 重建术后患者进行肌力评估的过程中, 不仅要关注双侧的对称性, 更要注意与健康对照者进行对比分析。

本研究还发现股, 四头肌离心收缩肌力特征与向心收缩时不同, 只有在屈膝 30°时, ACL 重建者重建侧的 Qe 与健康人群存在差异; ACL 重建者的 Qe 峰值以及在屈膝 60°, 70°和 80°时的 Qe 存在不对称特征, 即重建侧仅与对侧存在差异, 而在屈膝 40°和 50°时, 未发现与健康人群或对侧的差异。Arms 等[24]曾报道, 当膝关节屈曲角度为 0°~45°时, 股四头肌收缩会显著地增加 ACL 应力。此外, 屈膝 30°是运动过程中保持膝关节稳定的重要位置状态, 并且在等速膝关节伸直过程中, ACL 受力峰值也出现在膝关节屈曲 35°~40°的位置[25]。以往也有基于核磁骨挫伤的研究报道, ACL 损伤发生期间膝关节的屈曲角度在 36°左右[26]。因此, 屈曲 30°时的离心肌力对评估实际运动过程中的肌肉功能有重要意义。综合上述结果, 可知股四头肌的力量特征存在角度特异性, 肌力峰值可能不能全面地代表肌肉功能状态, 还需关注不同屈膝角度时的特异性改变特征。与离心收缩模式相比, 屈膝 40°和 50°时, 股四头肌向心肌力更具特异性和灵敏性, 因此在评估患者的肌肉力量特征时, 可以将其作为关键的评估指标。在康复过程中, 不仅要重视肌力最大值的提升, 而且更要加强动作控制性训练, 强调特定角度下的肌肉功能恢复。

本文研究结果不完全支持第二个假设, 即 ACL重建侧腘绳肌肌力与对侧及健康对照者之间均存在显著差异, 且具有角度特异性。本文研究结果表明, 对于腘绳肌肌力, 在向心收缩和离心收缩模式下, ACL 重建者的 Hc 和 He 峰值及不同角度下的 Hc 和He 均与健康对照者无显著差异, 但都存在双侧不对称特征, 即重建侧的 Hc 和 He 显著小于对侧。研究结果表明, 腘绳肌的肌力总体上呈现为重建侧小于对侧, 峰值与不同角度下的肌力特征相似, 不存在角度特异性, 与以往研究结果相一致。Timmins 等[27]曾报道 ACL 重建术后重建侧腘绳肌离心收缩肌力显著小于对侧。Cristiani 等[28]针对 4000 多名患者进行研究, 发现仅 47%的患者腘绳肌等速肌力达到对称, 即双侧肌力对称指数超过 90%。腘绳肌收缩不仅可以使膝关节屈曲, 对防止胫骨过度前移也有重要作用, 与 ACL 的生理功能有协同作用。研究表明, 腘绳肌肌肉力量的降低会增加动作中的 ACL受力[29]。ACL 重建术后腘绳肌肌力不足比较常见, 在 ACL 损伤预防及伤后的康复过程中, 要同时增强离心和向心收缩模式下的肌力, 改善腘绳肌的肌肉功能, 对降低 ACL 损伤有重要意义[30]。

本文研究结果支持第三个假设, 即 ACL 重建侧腘绳肌与股四头肌肌力的比值与对侧及健康对照者之间均存在显著差异, 且具有角度特异性。本研究发现, 屈膝 40°和 50°时, ACL 重建侧的 Hc/Qc 均显著大于健康对照者, 但是与对侧无显著差异。ACL重建者呈现较大的屈伸肌力比值, 与以往的研究结果相似。Baumgart 等[31]曾探究 ACL 重建者等速向心肌力的角度特异性, 发现患者重建侧呈现较大的屈伸肌力比值, 且差异发生在屈膝 40°~60°之间。研究表明, 当屈膝角度低于 60°时, 股四头肌的收缩会使胫骨发生前向位移, 而腘绳肌的收缩能抑制胫骨向前的位移, 是维持膝关节动态稳定性的主要结构[32]。屈伸肌力比值也是临床上常用的评估运动员是否准备好重返运动的标准。有研究表明, 屈伸肌力比值可能与落地动作中膝关节受力以及前交叉韧带所受负荷有关[33]。Kyritsis 等[34]的研究结果也表明, 术后重返运动后, 膝关节屈伸力量比值的降低会显著增加前交叉韧带再受伤的风险。重建侧屈伸肌力比值增加可能是 ACL 重建术后肌肉收缩的代偿模式, 可以帮助控制胫骨前移, 维持膝关节的动态稳定性。

本研究不仅分析传统的屈伸肌力比值(Hc/Qc和 He/Qe), 还分析了功能性的屈伸肌力比值, 包括Hc/Qe (代表屈膝动作)和 He/Qc (代表伸膝动作), 以便更好地描述膝关节屈伸时主动肌与拮抗肌之间的关系。结果表明, ACL 重建者重建侧和对侧在 30°, 40°, 50°和 60°时的 Hc/Qe 均显著大于健康对照者, 但 ACL 重建者双侧下肢之间无显著差异。功能性的 Hc/Qe 类似落地时的屈膝缓冲动作, 在缓冲过程中, 股四头肌表现为离心收缩, 腘绳肌表现为向心收缩。当屈膝角度小于 60°时, ACL 重建者双侧下肢的缓冲能力可能比健康者更弱, 导致损伤的风险较高。所以, 在 ACL 重建术后康复的过程中, 不仅要加强重建侧较小角度下屈膝动作的控制训练, 也要改善对侧的缓冲控制能力。此外, 本研究还发现ACL 重建者的重建侧在 40°和 50°时的 He/Qc 均显著大于健康对照者, 但与对侧之间无显著差异。功能性的 He/Qc 类似伸膝踢球动作, 重建侧的 He/Qc增加, 说明患者的伸膝动作强度较低, 且这一特征主要体现为与健康对照者之间的差异。综上所述, 对于功能性屈伸肌力比值, 不仅要进行患者的双侧对称性分析, 还应该侧重分析患者与健康人群的差异性特征。

虽然本研究较全面地分析了 ACL 重建术后股四头肌和腘绳肌在不同角度下的特征, 但以后的研究中还应该同时采集肌肉的肌电信号, 分析不同角度下肌肉的激活状态, 进一步探究重建术后肌力不足的机理, 为康复策略提供更具体的建议。由于不同术式也会对康复效果产生影响, 本研究只探究了应用腘绳肌重建术后的等速肌力角度特异性特征, 今后应该进一步分析应用不同术式患者的肌力特征。此外, 虽然本研究测得的健康对照组的股四头肌与腘绳肌肌力值与以往报道的健康人的肌力数值[35–37]相当, 但本研究的样本量相对较小, 未来的研究中需要进一步增加样本量, 并建立健康人群肌力的数据库, 为评估患者的肌力恢复状态提供更坚实的参考依据。

本研究分析了 ACL 重建术后 12 个月患者不同屈膝角度时的等速肌力特征, 发现不同角度下股四头肌的等速肌力特征不同, 呈现角度特异性, 重建侧屈膝 40°和 50°时的股四头肌等速肌力显著小于对侧和健康对照者。腘绳肌肌力在不同角度下的特征相似, 重建侧仅与对侧呈现差异, 与健康对照者无显著差异。传统和功能性腘绳肌与股四头肌力量比值均具有角度特异性, 重建侧屈膝 40°和 50°时的 Hc/Qc 和 He/Qc 均显著大于健康对照者, 重建侧和对侧屈膝 30°, 40°, 50°和 60°时的 Hc/Qe 均显著大于健康对照者。研究结果表明, 康复过程中, 对于股四头肌等速肌力, 不仅要关注其与对侧的差异, 也要关注其是否恢复到健康者的水平; 而对于屈伸肌力比值, 主要关注其是否恢复到健康者的状态。

参考文献

[1] Wiggins A J, Grandhi R K, Schneider D K, et al. Risk of secondary injury in younger athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine, 2016, 44(7): 1861–1876

[2] Oiestad B E, Holm I, Aune A K, et al. Knee function and prevalence of knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective study with 10 to 15 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med, 2010, 38(11): 2201–2210

[3] Otzel D M, Chow J W, Tillman M D. Long-term defi-cits in quadriceps strength and activation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport, 2015, 16(1): 22–28

[4] Lewek M, Rudolph K, Axe M, et al. The effect of insufficient quadriceps strength on gait after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech (Bris-tol, Avon), 2002, 17(1): 56–63

[5] Keays S L, Bullock-Saxton J E, Newcombe P, et al. The relationship between knee strength and functional stability before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Res, 2003, 21(2): 231–237

[6] Crotty N M N, Daniels K A J, McFadden C, et al. Relationship between isokinetic knee strength and single-leg drop jump performance 9 months after ACL reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med, 2022, 10(1): 23259671211063800

[7] Fischer F, Blank C, Dünnwald T, et al. Isokinetic extension strength is associated with single-leg verti-cal jump height. Orthop J Sports Med, 2017, 5(11): 2325967117736766

[8] Palmieri-Smith R M, Curran M T, Garcia S A, et al. Factors that predict sagittal plane knee biomechanical symmetry after anterior cruciate ligament reconst-ruction: a decision tree analysis. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 2022, 4(2):167–175

[9] Sturnieks D L, Besier T F, Hamer P W, et al. Knee strength and knee adduction moments following arth-roscopic partial meniscectomy. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2008, 40(6): 991–997

[10] Tourville T W, Jarrell K M, Naud S, et al. Relationship between isokinetic strength and tibiofemoral joint space width changes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med, 2014, 42(2): 302–311

[11] Ardern C L, Webster K E, Taylor N F, et al. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruc-tion surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med, 2011, 45(7): 596–606

[12] Gokeler A, Welling W, Zaffagnini S, et al. Develop-ment of a test battery to enhance safe return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2017, 25(1): 192–199

[13] Zwolski C, Schmitt L C, Quatman-Yates C, et al. The influence of quadriceps strength asymmetry on patient-reported function at time of return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med, 2015, 43(9): 2242–2249

[14] Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, et al. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL co-hort study. Br J Sports Med, 2016, 50(13): 804–808

[15] Shi H, Huang H, Ren S, et al. The relationship be-tween quadriceps strength asymmetry and knee bio-mechanics asymmetry during walking in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Gait Posture, 2019, 73: 74–79

[16] Burgi C R, Peters S, Ardern C L, et al. Which criteria are used to clear patients to return to sport after primary ACL reconstruction? A scoping review. Br J Sports Med, 2019, 53(18): 1154–1161

[17] Ithurburn M P, Altenburger A R, Thomas S, et al. Young athletes after ACL reconstruction with quadric-ceps strength asymmetry at the time of return-to-sport demonstrate decreased knee function 1 year later. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2018, 26(2): 426–433

[18] Riesterer J, Mauch M, Paul J, et al. Relationship between pre- and post-operative isokinetic strength after ACL reconstruction using hamstring autograft. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 2020, 12(1): 68

[19] Coombs R, Garbutt G. Developments in the use of the hamstring/quadriceps ratio for the assessment of mus-cle balance. J Sports Sci Med, 2002, 1(3): 56–62

[20] Huang H, Guo J, Yang J, et al. Isokinetic angle-specific moments and ratios characterizing hamstring and quadriceps strength in anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 7269

[21] 黄红拾, 蒋艳芳, 杨洁, 等. 膝关节30°时前交叉韧带断裂对等速屈伸肌力比值的影响. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2015, 47(5): 787–790

[22] Baumgart C, Welling W, Hoppe MW, et al. Angle-specific analysis of isokinetic quadriceps and hamst-ring torques and ratios in patients after ACL-recons-truction. BMC Sports Science, Medicine & Rehabili-tation, 2018, 10: 23

[23] Brown C, Marinko L, LaValley M P, et al. Quadriceps strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruc-tion compared with uninjured matched controls: a sys-tematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med, 2021, 9(4): 2325967121991534

[24] Arms S W, Pope M H, Johnson R J, et al. The bio-mechanics of anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation and reconstruction. Am J Sports Med, 1984, 12(1): 8–18

[25] Toutoungi D E, Lu T W, Leardini A, et al. Cruciate ligament forces in the human knee during rehabilita-tion exercises. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon), 2000, 15(3): 176–187

[26] Shi H, Ding L, Ren S, et al. Prediction of knee kinematics at the time of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries based on the bone bruises. Ann Biomed Eng, 2021, 49(1): 162–170

[27] Timmins R G, Bourne M N, Shield A J, et al. Biceps femoris architecture and strength in athletes with a previous anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2016, 48(3): 337–345

[28] Cristiani R, Mikkelsen C, Forssblad M, et al. Only one patient out of five achieves symmetrical knee function 6 months after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2019, 27(11): 3461–3470

[29] Weinhandl J T, Earl-Boehm J E, Ebersole K T, et al. Reduced hamstring strength increases anterior cruciate ligament loading during anticipated sidestep cutting. Clin Biomech, 2014, 29(7): 752–759

[30] Buckthorpe M, Danelon F, La Rosa G, et al. Recom-mendations for hamstring function recovery after ACL reconstruction. Sports Med, 2021, 51(4): 607–624

[31] Baumgart C, Welling W, Hoppe M W, et al. Angle-specific analysis of isokinetic quadriceps and hamst-ring torques and ratios in patients after ACL-reconst-ruction. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabili-tation, 2018, 10(1): 1–8

[32] Almosnino S, Brandon S C, Day A G, et al. Principal component modeling of isokinetic moment curves for discriminating between the injured and healthy knees of unilateral ACL deficient patients. J Electromyogr Kinesiol, 2014, 24(1): 134–143

[33] Heinert B L, Collins T, Tehan C, et al. Effect of hamstring-to-quadriceps ratio on knee forces in fema-les during landing. Int J Sports Med, 2021, 42(3): 264–269

[34] Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P, et al. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med, 2016, 50(15): 946–951

[35] Leyva A, Balachandran A, Signorile J F. Lower-body torque and power declines across six decades in three hundred fifty-seven men and women: a cross-section-al study with normative values. J Strength Cond Res, 2016, 30(1): 141–158

[36] Sole G, Hamrén J, Milosavljevic S, et al. Test-retest reliability of isokinetic knee extension and flexion. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2007, 88(5): 626–631

[37] Šarabon N, Kozinc Ž, Perman M. Establishing refe-rence values for isometric knee extension and flexion strength. Front Physiol, 2021, 12: 767941

Characteristics of Isokinetic Strength of Thigh Muscles 12 Months after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Abstract In order to investigate the isokinetic strength of the thigh muscles at different knee flexion angles in patients 12 months after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, an open-chain concentric and eccentric tests of the quadriceps and hamstring were performed at an angular velocity of 60°/s in 16 males 12 months after ACL reconstruction and 14 healthy controls. The peak muscle strength of different contraction patterns at different knee flexion angles were analyzed and the following ratios were calculated: the concentric ratio of hamstring to quadriceps (Hc/Qc), the eccentric ratio of hamstring to quadriceps (He/Qe), the eccentric ratio of hamstring to the concentric ratio of quadriceps (He/Qc), and the concentric ratio of hamstring to the eccentric ratio of quadriceps (Hc/Qe). A two-way ANOVA with mixed design was used to examine the effects of groups and legs on isokinetic muscle strength characteristics. The following results can be concluded. The hamstring strength characteristics were similar at different knee flexion angles, with the reconstructed leg being significantly smaller than the contralateral leg and not different from the healthy controls. In contrast, the isokinetic quadriceps strength showed angle specificity, and the concentric quadriceps strength of the reconstructed leg at 40° and 50° of knee flexion differed not only from the contralateral leg but also from the healthy control leg, making it a more specific index for assessing muscle strength characteristics. Attention should be paid not only to bilateral symmetry but also to whether it is restored to the level of healthy individuals, emphasizing the recovery of muscle function at specific angles in rehabilitation. The flexion-extension strength ratios of bilateral lower limbs at smaller flexion angles differed from those of healthy controls, suggesting that postoperative rehabilitation should strengthen the control training of knee flexion movements of the reconstructed leg and improve the cushioning control ability of the contralateral leg.

Key words anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; isokinetic strength; quadriceps; hamstring; rehabilitation